Menu

Malaria Consortium conducted a study of the integration of vitamin A supplementation with seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) campaigns.

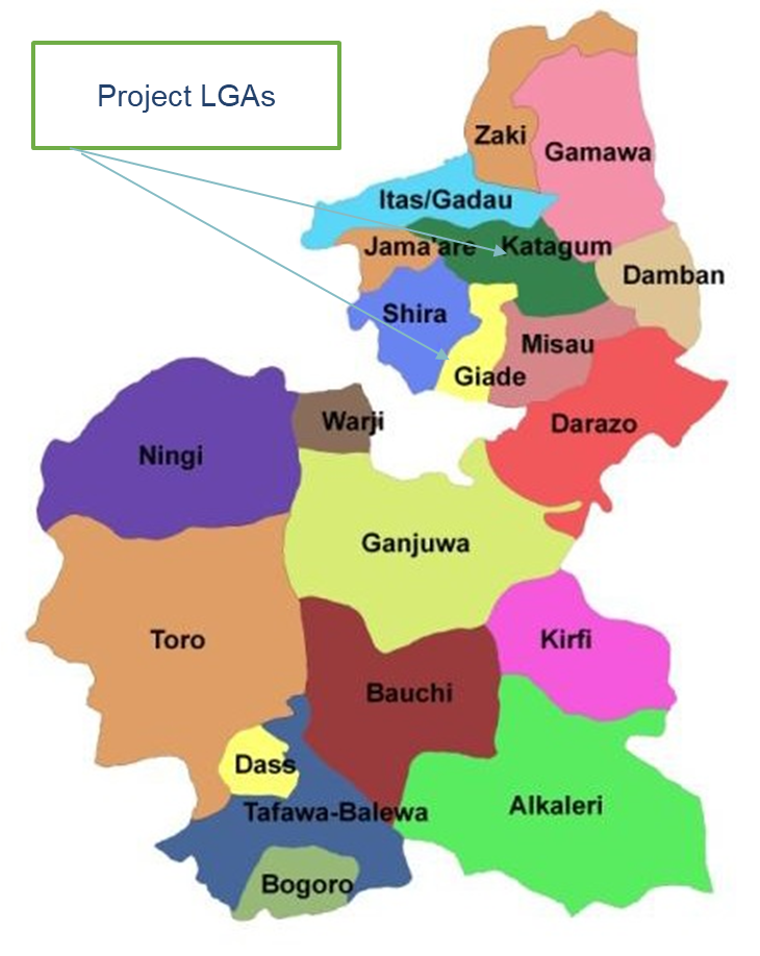

Giade (rural) and Katagum (urban) in Bauchi state

Malaria Consortium carried out a study to test the integration of vitamin A supplementation (VAS) with seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) campaigns in Giade (rural) and Katagum (urban) LGA in Bauchi state between May and December 2021. The purpose was to provide a body of evidence to support policy makers’ decision-making regarding full integration of VAS with SMC campaigns at scale and in diverse settings

The study was co-designed with key stakeholders including the National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP), the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control; the Department of Planning Research and Statistics; the Bauchi State Malaria Elimination Programme and the State Primary Health Care Development Agency.

VAS coverage increased from 1.2% at baseline to 82.3% at endline (with SMC integration), while SMC coverage stayed high at 90%. SMC quality was maintained and the integration was safe, and equitable.

The total cost per child receiving only SMC at baseline was $0.94, while total cost per child receiving both Vitamin A and SMC at endline was $1.18.

Scroll down for more key findings.

Dr. Olusola Oresanya, Senior Country Technical Coordinator, Malaria Consortiumm, shared the results of the study during an HCE Test & Learn session.

The following points are also considered implications for policy research. See the research brief for specific practices for this project.